Photo 1: Street view of the Maldives by cattan2011 used under Creative Common License CC BY 2.0 DEED

ORB International prides itself on its ability to conduct research in complex and dynamic environments around the globe. To work in such environments, we are often tasked with recruiting hard-to-survey populations. Members of these populations are often excluded from international surveys due to challenges sampling, recruiting, persuading, and interviewing them. But by excluding their voices, much international research is limited in its breadth, depth, and nuanced understanding of the most pressing issues facing the world today. Below, ORB shares its best practices for researching hard-to-survey populations using one of our recent studies in the Maldives as an example.

What are hard-to-survey populations?

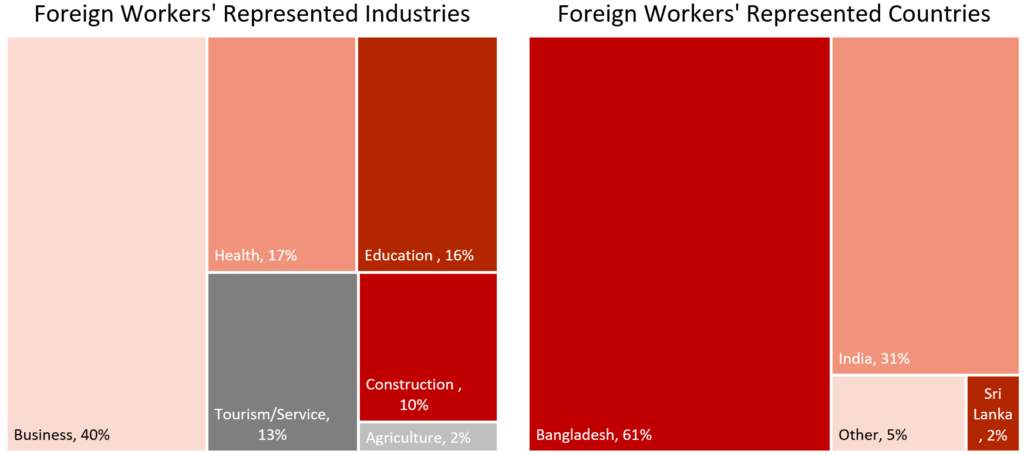

Populations are considered hard-to-survey if they require more time, effort, or resources to include in a sample than “average” general population respondents. This could be due to one of several reasons, including difficulties building a representative sample frame for the population, challenges reaching members of the population, or difficulties interviewing members of the population, among many others. More detailed descriptions of reasons populations could be hard-to-survey are outlined in the graphic below:

Figure 1: Types of Hard-to-Survey Populations

A look at the Maldives

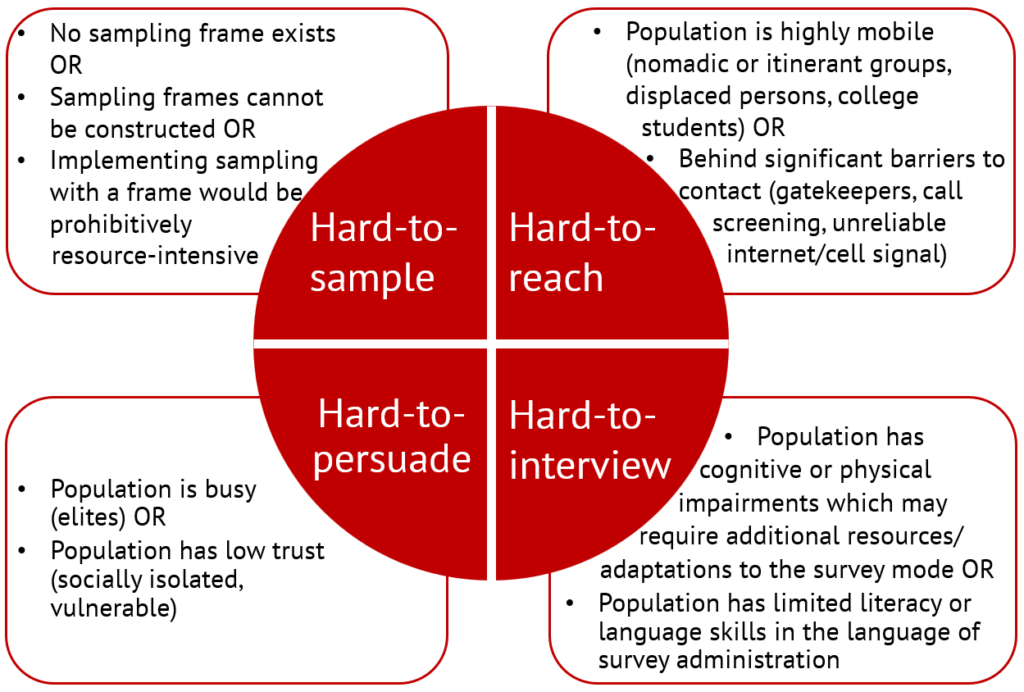

ORB conducted a study in the Maldives in 2022 to understand public perceptions of seaport and airport security. As part of this study, we recruited and interviewed 300 foreign workers, a rapidly growing population that is difficult to locate, track, and interview. Foreign workers in the Maldives have increased in number from just 2,422 in 1985 to 180,000 in 2020. They now represent a third of the country’s total population.1 Additionally, an estimated third of foreign workers in the Maldives (approx. 63,000) are undocumented.2 Most foreign workers in the Maldives are from Bangladesh, followed by India, Sri Lanka, and other South Asian countries.3 They are mostly young men between the ages of 20-35 and they are concentrated in the construction, health, and tourism industries.

As we developed our methodology for the study, we noted that foreign workers in the Maldives match several definitions of a hard-to-survey population, including:

- Hard-to-sample: Records of foreign workers are often incomplete and inaccurate. Maldivian census data likely underestimates foreign worker presence in the country, as many workers are undocumented and may not willingly participate in census surveys. Additionally, the latest census report from the Maldives (conducted in 2014) does not specify which countries foreign nationals originate from, making it difficult to build a representative sample that includes foreign workers.

- Hard-to-reach: Foreign workers are spread across many industries and atolls. During the workday, they are subject to schedules set by their employers and may not be available to participate in an interview. Additionally, many foreign workers, especially those in the construction industry, reside in large dormitories, which may be missed by enumerators through random household selection methods.

- Hard-to-persuade: Foreign workers are wary of surveys and have limited free time. Because many foreign workers in the Maldives are undocumented, they may be unwilling to participate in a survey for fear that they may be exploited by the Maldivian government or another institution that seeks to identify and deport them. Additionally, even foreign workers who are documented may not be able to take a half hour away from their jobs to participate in a survey.

- Hard-to-interview: Language barriers make interviewing many foreign workers impossible. Most foreign workers in the Maldives are from Bangladesh and have varying levels of fluency in Dhivehi, the local language. Finding trained enumerators who are fluent in Bengali (the native language in Bangladesh), but also able to participate in an enumerator training in Dhivehi, presents an additional challenge.

ORB’s Methodology

ORB and our local research team developed several methods to overcome the barriers involved with recruiting and interviewing foreign workers. As the study developed, we modified and evolved our strategies to achieve an even more representative sample.

Sampling foreign workers: To achieve our desired sample of 300 foreign workers, we first defined foreign workers, developed a sample frame, allocated interviews across atolls, and redistributed interviews as we gained more on-the-ground understanding of population distribution. We defined foreign workers as Third Country Nationals (TCNs) who, at the time the survey was conducted, had lived in the Maldives for a minimum period of three months and a maximum period of ten years. Next, we used 2014 Maldivian census data to distribute foreign worker interviews across the five atolls selected for the study. We then allocated interviews among the atolls (Figure 2). Finally, we reallocated 20 interviews from Haa Alif and Haa Dhaalu atolls to Kaafu atoll account for a lower than anticipated presence of foreign workers there.

Reaching foreign workers: ORB’s strategy for reaching foreign workers evolved over the course of the study. First, we tried reaching foreign workers by travelling to worksites and dormitories in each atoll. Enumerators used a random skip pattern to select a room within a dormitory or an area within a worksite. They then listed up to 15 foreign workers from each room or work area in their tablet, which then randomly selected a respondent to be interviewed.

However, enumerators encountered increasingly low response rates from foreign workers who could not be pulled away from their worksites during the day to be interviewed. Our local team initially suggested targeting foreign workers who frequent public parks in the evening, but we decided that this sampling approach would introduce bias by favoring foreign workers who have free time at the end of their workdays.

For this reason, enumerators eventually adopted the approach of targeting a few worksites and collecting foreign workers’ phone numbers so that they could follow up later to complete the interviews. Enumerators then implemented a snowball methodology, asking each respondent to refer them to up to five additional foreign workers to be interviewed via phone.

Persuading foreign workers: ORB was able to convince respondents to participate through after-hours phone interviews and by assuring anonymity for undocumented workers. No personal identifiable information was collected from any foreign worker, nor did any topics in the survey relate to immigration and/or citizenship status. Additionally, enumerators informed foreign workers that they could revoke their participation in the survey at any time. These measures provided the respondents with a sense of security that ultimately motivated them to participate in the survey.

Interviewing foreign workers: After an extensive search, ORB was able to recruit two university student who were fluent in both Dhivehi and Bengali. These enumerators were able to interview foreign workers from Bangladesh, thereby broadening the diversity of our respondent pool. Without these two enumerators, our sample would have been constrained to foreign workers who had been in the Maldives long enough to have learned Dhivehi and who, therefore, could have more similar perspectives to those of Maldivian citizens.

By implementing these sampling, recruiting, and interviewing methods, ORB was able to complete 304 foreign worker interviews across all five atolls from a range of countries and industries, as outlined below:

Figure 2: Achieved Foreign Worker Sample by Industry & Country of Origin – 2022 Maldives Study

*Percentages calculated from a total of 304 foreign worker respondents.

Conclusion

ORB was able to achieve the desired sample size for a sub-population that was hard-to-survey in many ways by employing country-specific strategies that evolved as the project developed. Each aspect of recruiting foreign workers in the Maldives presented its own unique challenge. Maldivian census data allowed us to allocate foreign worker interviews proportionally across atoll; however, we were unable to allocate interviews proportionally by foreign workers’ countries of origin or represented industries. Implementing a snowball methodology proved to be an effective way of reaching foreign workers across different industries, but only having enumerators who spoke Dhivehi and Bengali excluded some respondents from India, the Philippines, and other South Asian nations. For future surveys in the Maldives, triangulating Maldivian census data with data from other surveys would allow us to set quotas to achieve proportional representation from foreign workers’ countries of origin and represented industries. Recruiting additional enumerators who are fluent in other South Asian languages would also allow us to broaden our respondent pool.

ORB International continues to strive to include hard-to-survey populations in surveys in the Maldives and beyond so that their unique perspectives can help inform future policies and programs in their communities. For more findings from our 2022 Maldives survey, click here. To learn more about how ORB International conducts research in multilingual environments, click here.

_____________________________________

1 Protecting Migrant Workers in Maldives, International Labour Organization, 2021

2 Preliminary Report: Study on Socio-Economic aspects of COVID-19 in the Maldives (Round Two), United Nations Maldives, 2020

3 Country Profiles: Maldive Islands – Integral Human Development