By Victoria Smith and Philippe Bone

This International Women’s Day, over two decades after the United Nations passed Resolution 1325 on women, peace, and security, ORB International reflects on its thematic exploration on women-led peace initiatives in Nigeria’s BAY states.

Northeastern Nigeria is no stranger to conflict. Over the past decade, communities in the Borno, Adamawa, and Yobe (BAY) states have suffered violence from the Boko Haram insurgency, farmer-herder conflicts, organized crime, and social devastation in the wake of natural disasters. While these problems impact all members of society, women are particularly vulnerable. Breakdown of social order does not only leave women at an increased risk of physical and sexual violence; the daily tribulations of being a woman and caring for one’s family are made more difficult when there is no food to feed one’s children, or when there is no hospital to go to when medical care is needed. The death of a husband or father can leave women and their families especially vulnerable to poverty; in the words of a woman from Adamawa: “If your husband is killed during the conflict, it is the same as if the woman is also killed.” As a result, women are undoubtedly key stakeholders when it comes to addressing the cyclical roots of conflict and its effects on their communities.

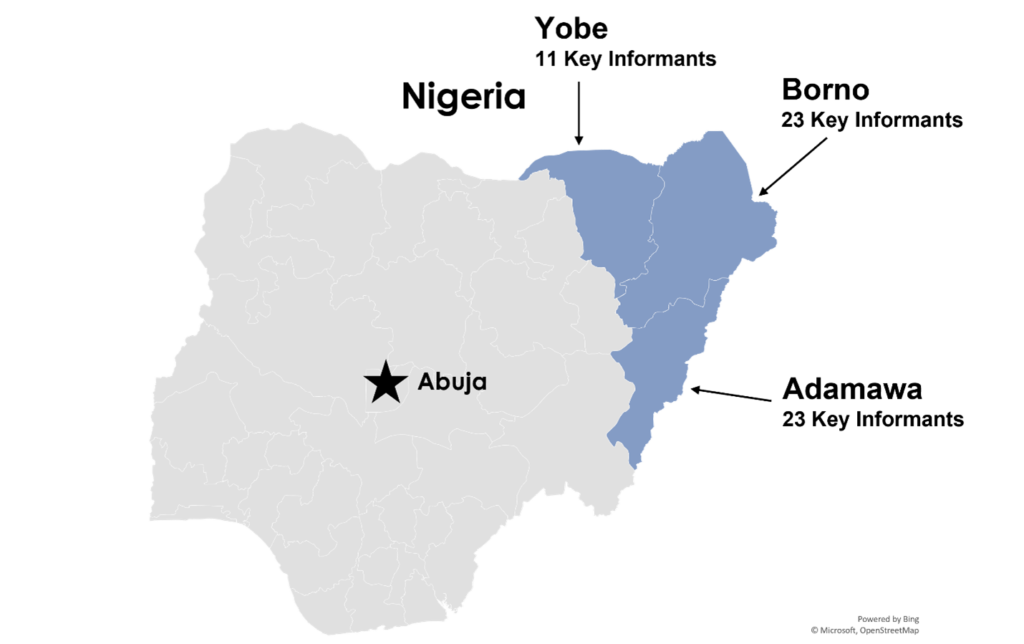

To better understand women’s roles and experiences in supporting conflict resilience and peace, ORB conducted 57 qualitative, semi-structured interviews with women in the BAY states. These women held different positions of leadership in their community, ranging from political organizers, healthcare providers, small business owners, and traditional leaders. ORB also took care to include the voices of women representatives from the Fulani community, a group that is sometimes marginalized in the BAY states. From these qualitative in-depth interviews, ORB gained valuable insight on the mechanisms that women build to prevent and alleviate conflict in their communities. This includes:

- Women in the BAY states have developed nonviolent methods for resolving conflicts.

- Women in the BAY states identify and engage with members of their communities vulnerable to recruitment by VEOs (violent extremist organizations).

- Women in the BAY states support each other to fill resource gaps.

- Development of women’s networks to mediate conflict.

The combination of population growth and destruction caused by extreme climate events has put serious pressure on available land resources in the BAY states. Farmers have expanded their fields beyond traditional farmland and into the bush to meet the needs of their families and the growing population. These changes in land use are often in direct conflict with transhumant Fulani herders, who return to the BAY states as part of their annual herding route to find traditional pastures, which are now used for growing crops. As the herders make their way through the BAY states, livestock may trample a farmer’s field, and the situation can turn violent. A woman from Adamawa explains: “…The Fulani will come near pretending to be gazing on uncultivated lands, but along the line they will end up grazing all our crops in the farmlands. If you want to chase them away… that will lead to trouble… They can burn your houses and destroy all your farmland.” Farmer-herder violence is not one-sided; herders also fear that farmers will attack them as they move their livestock. The violence has engulfed many communities in the BAY states: some years, farmer-herder conflicts kill more people than Boko Haram activities.

When violence erupts, women (as individuals and in groups) directly engage in conflict resolution efforts by utilizing their roles and attributes as women. During in-depth interviews, women expressed they have “wisdom” and “foresight” in analyzing an incident and explain that their more conciliatory style of communication helps to de-escalate tensions. Once a situation has calmed, they clarify points of the incident and counsel those involved on just financial compensation for the victim(s). Women also seek to prevent reprisals for a violent incident by going to women in the opposite camp (typically, members of farming communities seek out the migrant Fulani, but not always). The parties discuss the mutual desire for women across ethnic groups to have healthy families and peaceful lives. They seek to understand the root of the problems facing their communities, then advise on how to avoid conflicts in the future. As a Fulani woman from Adamawa explains her discussions with members of the resident farming community: “When they come to us…we will sit together to make necessary discussions. When I return home, I will gather the women and tell them what we have discussed with other people, so that we can have peaceful coexistence amongst the herdsmen and the farmers.”

- Engagement and education of at-risk youth.

Many of the women that participated in ORB’s study in the BAY states identified youth unemployment and drug addiction as key vulnerabilities to violent extremism and crime in their communities. Interview respondents link high rates of unemployment to idleness, drug addiction (usually tramadol, an opioid), and crime. According to a woman from Borno: “For those who are unemployed, idle, and have no formal education, if they know that the VEOs give him money…he will just follow the VEOs to wherever they are going to go.” Additionally, to cope with social isolation and the trauma of living in a community in conflict, youth often turn to tramadol. VEOs prey on these vulnerable, drug-addicted youths for recruitment, and use their addiction to goad young men into committing acts of brutality too shocking for most sober minds.

At the local level in Nigeria’s BAY states, women directly engage with at risk-youth and educate them about the path from addiction and idleness to criminal activity and violent extremism. They also explain to children and youth the consequences of criminal activity on one’s future, and specifically warn them against joining extremist groups like Boko Haram. Instead of having men counsel the youth about behavior, women appeal to their roles as mothers and go into the community to talk to youth about the dangers of crime and drug addictions while explaining what constitutes right conduct. The way this engagement occurs is different across the region. Sometimes, women will engage these youths alone; they start friendly conversations with at-risk youth and refer to their shared community ties to develop an ethos with them before discussing harder topics. Other times, women work together via organizations. A woman in Borno explains: “We organize gatherings for our youths, and we admonish them that we are all one people, and that they shouldn’t get involved in political violence. We often tell them that politics will come and go, but we would always remain a community.”

- Fulfilling resource and economic gaps.

Across the BAY states, women report developing and leveraging community networks to strengthen their urban neighborhoods and rural villages against daily hardships that feed cycles of poverty and violence. Poverty is a key driverand consequence of insurgency and crime in the BAY states. ORB’s research found that violent conflict impacted the economies of BAY state communities via the destruction of capital (including crops and livestock) and prevention of people from accessing markets. As a result, people could not engage in commerce and sell their goods, and often could not even feed themselves. Adding to the economic woes of BAY state communities is the inflation of the Naira, which has made necessities costly for many families. According to a woman from Yobe: “The things you usually in the past, presently it has multiplied three or even four times higher than it was in the past. And sometimes the prices go higher than that…People are really suffering and in a difficult situation.”

To create a barrier against the threat of poverty, women have utilized their community organizations and social networks to create community self-help funds. Members of these organizations pool their money and resources together to provide aid to vulnerable members in their communities. Sometimes, these funds are for specific causes related to women. For example, a farmer’s association for women in Borno collects money for women whose farming capital is low. Similarly, a community in Yobe collects a voluntary contribution of 500 Naira from members when a woman gives birth; the woman can do with this money whatever she wishes but will typically use it to invest in her own small business and develop her financial independence. These women’s organizations view the development of a woman’s economic independence as a means for her to further engage in her community in a constructive way. As a leader from a woman’s organization in Borno explains: “That is the reason why we came up with this association, so that we can stand as women and make sure that women are involved in whatever is going on in the community, be it business, be it politics, be it education, be it job opportunities.”

Conclusion

Communities where women develop robust social networks are more resilient communities. In Nigeria’s BAY states, women have taken leading roles in preventing and mitigating the effects of violent extremism and conflict by fomenting community relationships and enhancing community capacity to resolve disputes. As society’s mothers, caregivers, and homemakers, these women also fill a vital knowledge gap on community needs frequently neglected in male-dominated environments. By providing opportunities to address social and economic vulnerabilities, women-led initiatives ensure marginalized voices and concerns, often overlooked in agendas set up by men, are heard. While the above practices may be localized, it’s important that researchers, programmers, and funders alike understand their themes and mechanisms so that they may be scaled or replicated elsewhere.

UN Security Council, Security Council resolution 1325 (2000) , 31 October 2000, S/RES/1325 (2000), available at https://www.refworld.org/docid/3b00f4672e.html. Accessed 8 Mar. 2023.

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Nigeria Humanitarian Response Plan 2023 (February 2023), https://reliefweb.int/report/nigeria/nigeria-humanitarian-response-plan-2023-february-2023. Accessed 7 Mar. 2023.

Higazi, Adam. “Herders and Farmers in Nigeria: Coexistence, Conflict, and Insurgency.” ISPI, Italian Institute for International Political Studies, 19 Mar. 2020, https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/herders-and-farmers-nigeria-coexistence-conflict-and-insurgency-25447.

Brottem, Leif. Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 2021, The Growing Complexity of Farmer-Herder Conflict in West and Central Africa, https://africacenter.org/publication/growing-complexity-farmer-herder-conflict-west-central-africa/. Accessed 7 Mar. 2023.

International Crisis Group, 2018, Stopping Nigeria’s Spiralling Farmer-Herder Violence, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/262-stopping-nigerias-spiralling-farmer-herder-violence. Accessed 7 Mar. 2023.

Karami, Ali. “Opioid Painkiller Tramadol Abuse by Boko Haram and Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP).” MEMRI, Middle East Media Research Institute, 28 June 2021, https://www.memri.org/reports/opioid-painkiller-tramadol-abuse-boko-haram-and-islamic-state-west-africa-province-iswap.

Evans, Olaniyi, and Ikechukwu Kelikume. “The Impact of Poverty, Unemployment, Inequality, Corruption and Poor Governance on Niger Delta Militancy, Boko Haram Terrorism and Fulani Herdsmen Attacks in Nigeria.” International Journal of Management, Economics and Social Sciences, vol. 8, no. 2, 2019, https://doi.org/10.32327/ijmess/8.2.2019.5.

Oyekanmi, Samuel, and Emmanuel Anwanaodung. “Nigeria’s Inflation Rate Rises to 21.82% in January 2023.” Nairametrics, 15 Feb. 2023, https://nairametrics.com/2023/02/15/nigerias-inflation-rate-rises-to-21-82-in-january-2023/.